In a lecture theatre that once featured in the movie Inception, Sebastian Riedel discusses how that particular film didn’t make any sense:

“It’s not internally consistent. There are points where a person falls in dream level L+1 but fails to wake up in dream level L”.

This isn’t a film club but is instead this week's launch of UCL’s NLP group, a loose association of faculty members, alumni and others interested in NLP research in London. Riedel is bemoaning that whilst we have become reasonably good at building machine learning (ML) models to recommend films based on people’s viewing history (Netflix knows it’s pretty likely I’ll watch Inception again), we haven’t made much progress on building models that can reason over unstructured data: Netflix cannot comment on the consistency of film plots.

Knowledge base construction

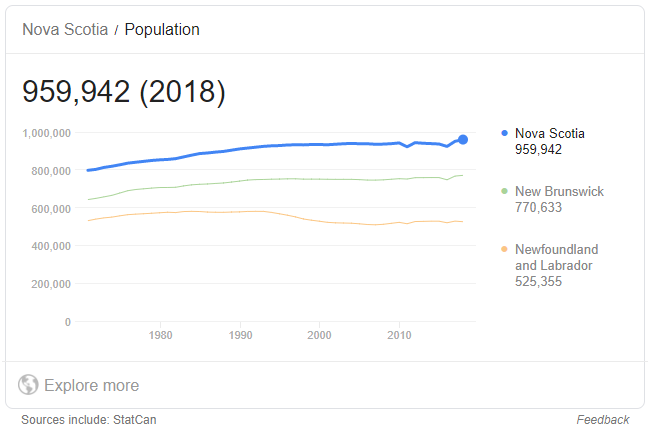

This leads to the central topic of Riedel’s keynote talk: UCL’s recent work in knowledge base construction. A knowledge base is a set of structured information (usually in the form of a graph) which represents entities (and the relationships between those entities) that have been extracted from unstructured sources. They are what allows Google to answer simple questions about the world: when I search “What is the population of Nova Scotia?”, Google can look up Nova Scotia in its knowledge graph, query the population relationship and return the answer “959,942”. The ability to query data in this way would be useful in all sorts of industries, not least law (think disclosure, research and matter management).

Building a knowledge base by hand is enormously time consuming (and clearly counter-productive if you only want to query your data in respect of a particular project - e.g. in disclosure), so finding methods for automatically constructing them is a hot area of research. Typical approaches split the problem into a pipeline of tasks: identify relevant entities in the texts (like cities and countries), cluster other references to those entities, identify semantic relationships between entities (like capitals, populations) etc. Each of these steps hides a mountain of complexity and the results are usually not good enough to use without manual review.

Enter BERT

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) is a language model developed by Google AI. Other language models are available, see e.g., ELMo from AllenNLP and ERNIE from Baidu (naming models after Sesame Street characters is considered very witty in ML circles). It’s a key step in the project to bring transfer learning to NLP. The goal of a language model is to predict how likely a sequence of words is. It should conclude that phrases like “The train was delayed because of leaves on the track” are fairly probable, whereas phrases like “Colourless green ideas sleep furiously” are not. BERT was built by training a model to try and predict missing words from their context: it is provided with lots of examples like “The [Blank] was delayed because of leaves on the track” and it tries to predict the word that has been removed.

What Riedel has been investigating is whether the language model learnt by BERT can work like a knowledge base. Given BERT has been trained on (a subset of) the internet, can we give it as an input “The population of Nova Scotia is [Blank]” and recover the correct answer? It turns out BERT performs fairly well at this (or, at least, about as badly as baseline systems built using the pipeline methodology). That’s tantalising because, unlike with the pipeline method, language models are trained in an unsupervised way: there’s no need to spend time/money on acquiring labeled data to finesse the different models in the pipeline.

Lots more work is needed. BERT cannot, for example, be interrogated like a knowledge graph to understand why it gives the answers it gives. But in a world in which we are drowning in data, anything that hints towards how we can make that data work for us is worth pursuing.

/Passle/5badda5844de890788b571ce/SearchServiceImages/2024-04-23-09-28-50-380-66277f52e87bcfeefc961b68.jpg)

/Passle/5badda5844de890788b571ce/SearchServiceImages/2024-04-18-09-20-15-162-6620e5cfc42b62f07a0c9812.jpg)

/Passle/5badda5844de890788b571ce/SearchServiceImages/2024-04-16-09-00-11-721-661e3e1b4025ff662f68a125.jpg)

/Passle/5badda5844de890788b571ce/SearchServiceImages/2024-04-17-11-56-06-594-661fb8d69a562cbaeec6ef66.jpg)